California Confirms First Human Cases of Bird Flu Linked to Dairy Cattle

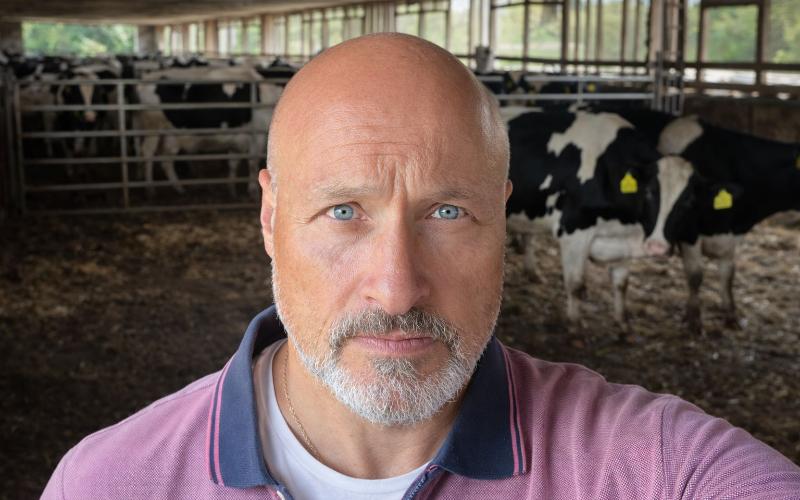

California health authorities confirmed the state’s first two human cases of avian influenza (bird flu) on October 3, marking a significant development in the ongoing management of zoonotic diseases in agricultural regions.

Both individuals, residents of California’s Central Valley—an agricultural hub—contracted the virus after contact with infected dairy cattle. The cases were verified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), according to the California Department of Public Health.

The health department emphasized that there is no known connection between the two individuals, indicating only animal-to-human transmission of the virus within California. Both patients exhibited mild symptoms, including conjunctivitis, but neither experienced respiratory complications, nor required hospitalization.

While health officials remain cautious, the overall risk to the public remains low. However, those who frequently interact with livestock, such as dairy and poultry workers, face heightened risks. The state's agricultural workers identified bird flu in over 40 dairy cow herds in September, following a national trend of avian influenza outbreaks across 14 states since March, as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Avian influenza, typically lethal to poultry, has also impacted dairy herds. Although the virus has a low mortality rate of 2% in dairy cattle, the disease can significantly reduce milk production and lead to thicker, discolored milk. Several farms have culled hundreds of cows after they failed to recover production levels post-infection, the USDA noted.

Despite these challenges, health officials have reassured the public that pasteurized milk and dairy products remain safe for consumption, as the pasteurization process effectively eliminates the bird flu virus. Milk from infected cows is not allowed into the public milk supply.

The California Department of Public Health, in collaboration with state agricultural workers, has ramped up outreach efforts to inform dairy producers and farmworkers about preventive measures, including the use of protective equipment such as N95 masks, gloves, and eye protection. To date, the state has distributed more than 340,000 respirators, 1.3 million gloves, 160,000 face shields and goggles, and 168,000 hair coverings.

Health authorities advise individuals who have been in contact with infected animals to monitor their health for up to 10 days, watching for symptoms such as eye redness, coughing, fever, or fatigue. The state's continued vigilance underscores its commitment to mitigating the spread of avian influenza from animal populations to humans while protecting the agricultural workforce.

The health department emphasized that there is no known connection between the two individuals, indicating only animal-to-human transmission of the virus within California. Both patients exhibited mild symptoms, including conjunctivitis, but neither experienced respiratory complications, nor required hospitalization.

While health officials remain cautious, the overall risk to the public remains low. However, those who frequently interact with livestock, such as dairy and poultry workers, face heightened risks. The state's agricultural workers identified bird flu in over 40 dairy cow herds in September, following a national trend of avian influenza outbreaks across 14 states since March, as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Avian influenza, typically lethal to poultry, has also impacted dairy herds. Although the virus has a low mortality rate of 2% in dairy cattle, the disease can significantly reduce milk production and lead to thicker, discolored milk. Several farms have culled hundreds of cows after they failed to recover production levels post-infection, the USDA noted.

Despite these challenges, health officials have reassured the public that pasteurized milk and dairy products remain safe for consumption, as the pasteurization process effectively eliminates the bird flu virus. Milk from infected cows is not allowed into the public milk supply.

The California Department of Public Health, in collaboration with state agricultural workers, has ramped up outreach efforts to inform dairy producers and farmworkers about preventive measures, including the use of protective equipment such as N95 masks, gloves, and eye protection. To date, the state has distributed more than 340,000 respirators, 1.3 million gloves, 160,000 face shields and goggles, and 168,000 hair coverings.

Health authorities advise individuals who have been in contact with infected animals to monitor their health for up to 10 days, watching for symptoms such as eye redness, coughing, fever, or fatigue. The state's continued vigilance underscores its commitment to mitigating the spread of avian influenza from animal populations to humans while protecting the agricultural workforce.

Key News of the Week