Former Airline Pilot Turns Cheese Maverick in Cyprus Halloumi Battle

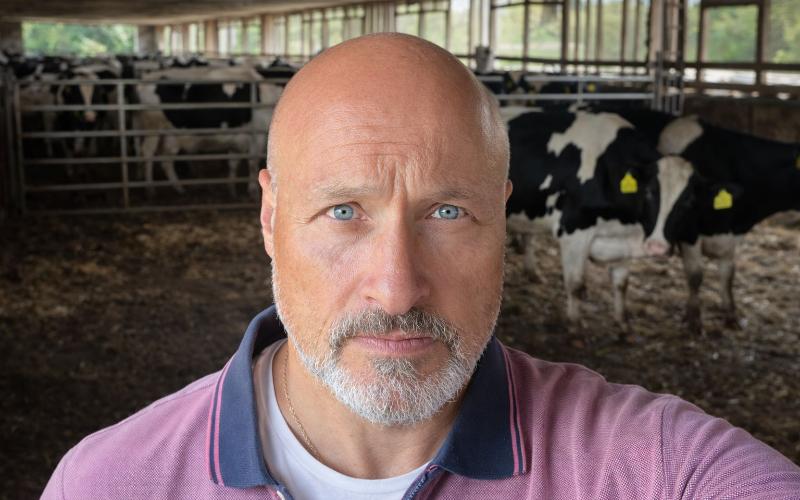

In the heart of Nicosia, Cyprus, a former airline pilot turned cheese entrepreneur is making waves with his traditional approach to Halloumi production. Pantelis Panteli, who took up cheese-making after being laid off from Cyprus Airways in 2013, has emerged as an unexpected advocate for the old ways in the midst of a heated legal dispute over the iconic cheese's ingredients.

While the Halloumi debate rages on, with conflicting opinions on whether it should be crafted from the milder cow's milk or the tangier blend of goat and ewe milk, Panteli remains steadfast in his commitment to the traditional method. Exclusively using ewe's milk, he has become a torchbearer for a fading tradition in the face of a changing industry.

"Nobody is making the real thing anymore, and that is our aim," Panteli asserted, standing amidst his flock of 300 sheep at his farm in Kokkinotrimithia, west of Nicosia. His journey into Halloumi-making began as an experiment guided by his mother-in-law, evolving into the establishment of his own 'Kouella' brand, named after the Cypriot term for ewe.

Despite operating with limitations – holding only a permit for direct consumer sales and a cap of 150 liters of milk production per day – Panteli has gained popularity through strategic use of social media. Leveraging platforms like TikTok and X, he informs customers of his locations, and within hours, his stock is typically sold out.

Halloumi, a versatile cheese that can be enjoyed raw, grilled, boiled, or fried without losing its form, holds significant economic importance for Cyprus as its largest export after pharmaceuticals. Panteli's meticulous process involves cooking milk with rennet, cutting and reheating the curdles, and finally, producing steaming hot slabs of Halloumi that quickly find eager buyers.

The broader dispute over Halloumi's ingredients has led to farmer demonstrations and industry stakeholders expressing concerns about the seasonal nature of ewe and goat's milk impacting production capacity. Despite Cyprus winning exclusive rights to produce and market the cheese with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) from the EU, tensions persist.

The conflict revolves around meeting the EU commitment to increase the use of ewe or goat milk to just over 50% by July 2024. With stakeholders citing the highly seasonal nature of these milks, a compromise to push back full compliance to 2029 is now under consideration.

Nicos Papakyriakou, director-general of the cattle breeders association, argues that the PDO should include cows' milk, pointing to an older 1985 trade standard that accepted it as an ingredient. He emphasizes that it is the mellower cows' milk that has enabled Halloumi to succeed in overseas markets.

"The PDO says it should smell like a farm," Papakyriakou remarked, referring to official specifications that Halloumi should have a 'barnyard' aroma. "It would smell like goats! What consumer abroad would buy that?" he questioned, encapsulating the essence of a dispute that goes beyond taste preferences to encompass economic considerations and market dynamics.

"Nobody is making the real thing anymore, and that is our aim," Panteli asserted, standing amidst his flock of 300 sheep at his farm in Kokkinotrimithia, west of Nicosia. His journey into Halloumi-making began as an experiment guided by his mother-in-law, evolving into the establishment of his own 'Kouella' brand, named after the Cypriot term for ewe.

Despite operating with limitations – holding only a permit for direct consumer sales and a cap of 150 liters of milk production per day – Panteli has gained popularity through strategic use of social media. Leveraging platforms like TikTok and X, he informs customers of his locations, and within hours, his stock is typically sold out.

Halloumi, a versatile cheese that can be enjoyed raw, grilled, boiled, or fried without losing its form, holds significant economic importance for Cyprus as its largest export after pharmaceuticals. Panteli's meticulous process involves cooking milk with rennet, cutting and reheating the curdles, and finally, producing steaming hot slabs of Halloumi that quickly find eager buyers.

The broader dispute over Halloumi's ingredients has led to farmer demonstrations and industry stakeholders expressing concerns about the seasonal nature of ewe and goat's milk impacting production capacity. Despite Cyprus winning exclusive rights to produce and market the cheese with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) from the EU, tensions persist.

The conflict revolves around meeting the EU commitment to increase the use of ewe or goat milk to just over 50% by July 2024. With stakeholders citing the highly seasonal nature of these milks, a compromise to push back full compliance to 2029 is now under consideration.

Nicos Papakyriakou, director-general of the cattle breeders association, argues that the PDO should include cows' milk, pointing to an older 1985 trade standard that accepted it as an ingredient. He emphasizes that it is the mellower cows' milk that has enabled Halloumi to succeed in overseas markets.

"The PDO says it should smell like a farm," Papakyriakou remarked, referring to official specifications that Halloumi should have a 'barnyard' aroma. "It would smell like goats! What consumer abroad would buy that?" he questioned, encapsulating the essence of a dispute that goes beyond taste preferences to encompass economic considerations and market dynamics.

Key News of the Week