FARMERS, MUCH LIKE CONSUMERS, ARE EXPERIENCING THE IMPACT OF INFLATION AND FEELING THE FINANCIAL STRAIN

Farmers, like consumers, are feeling the squeeze of inflation. In January, a Horizon poll asked New Zealanders what they thought were the top issues for new prime minister Chris Hipkins. Cost of living was number one (72%) followed by health (61%), crime (58%), the economy overall (54%) and then housing (53%). Climate change ranked eighth (35%).

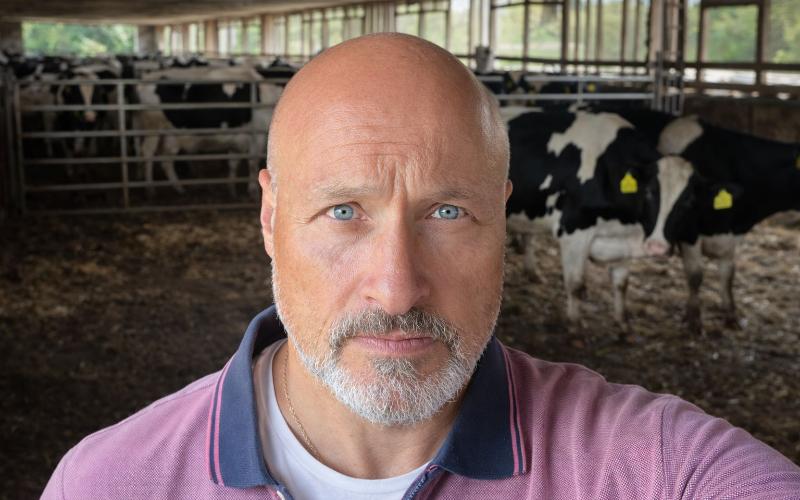

Dr Jacqueline Rowarth is an adjunct professor at Lincoln University. She is a farmer-elected director of DairyNZ and Ravensdown, and a producer-appointed member of Deer Industry New Zealand.

OPINION: Cost of living is the number one issue for New Zealanders. Whatever way one looks at it, whichever survey group or media outlet covers it, inflation is rampant, food prices are escalating, and more is being put on the credit card.

Electronic card spending was $19 billion in the March 2023 quarter, up almost 10% from the March 2022 quarter.

In January, a Horizon poll asked New Zealanders what they thought were the top issues for new prime minister Chris Hipkins. Cost of living was number one (72%) followed by health (61%), crime (58%), the economy overall (54%) and then housing (53%). Climate change ranked eighth (35%).

In February, an Ipsos poll of over 1000 people also found that cost of living (bracketed with inflation) topped the list of concerns, with almost two-thirds (65%) of people. Housing and crime ranked equal second (33%), while climate change ranked equal fourth with healthcare (27%).

Cost of living was twice as prevalent as any other issue.

This week, StatsNZ reported that the Food Price Index (FPI) showed an annual increase of 12.1% – higher than the previous month, which was the highest since September 1989.

In both months, grocery food was the largest contributor to the increased costs, with barn- or cage-raised eggs, potato chips and six-pack yoghurt the big drivers in the year to March. Barn- or cage-raised eggs, potato chips and cheddar cheese were the culprits the month before.

The biggest increases in actual costs were in fruit and vegetables, mostly weather driven. In March, the 22% increase reflected tomatoes, potatoes and avocados. In February, the 23% was driven by broccoli, tomatoes and lettuce. Potatoes increased by 48%, which then increases the price to processors of potato chips.

At the bottom of this pyramid – which goes from consumers at the top to supermarkets to processors – are the farmers and growers. Their costs of production are escalating faster than the prices they are being paid.

For dairy, which has featured in the FPI as both cheese and yoghurt, the costs of producing the milk are now estimated to be greater than the payout.

At the beginning of the season, Fonterra’s milk price estimate had a midpoint of $9.50 and costs of production were approximately $8.50, allowing money for repaying debt or investing in new technologies to increase productivity.

The milk price has reduced to $8.30 but costs have gone in the other direction. Part of the increase is in interest rates. Part of the cost is in the increased requirement for paperwork.

Questions must be asked: Is the increase in interest rates curbing inflation? Does the paperwork add value to the business?

The traditional anti-inflation tool is not working, perhaps because inflation wasn’t started in a traditional manner. Government borrowings during (and since) Covid lockdowns were made to keep the economy from collapsing.

It didn’t collapse, at least in part because the foundation of the economy is the primary sector. It kept on producing food, supporting the export economy – which brought money into the country.

The underlying cause of inflation, helpfully explained by the Reserve Bank, is usually that too much money is available to purchase too few goods and services, or that demand in the economy is outpacing supply.

The theory in curbing inflation is that putting up the interest rates will stop people borrowing. However, the increase in electronic card spending in the year to March suggests the message isn’t getting through to individuals.

For farmers and growers, it is. The $62.4b of borrowing in February 2020 (just before Covid lockdown) became $61.6b by February 2021 and $61.4b by February 2023.

However, whereas the debt in dairy has reduced by $2b over the past two years (to $36.5b), debt in sheep and beef farms has increased slightly to $15.2b, while debt in horticulture has increased substantially from $5.7b to $7.4b.

Income isn’t covering costs of production nor of improvements necessary to remain compliant with new regulations.

As for paperwork, farmers have estimated they are spending 30% of their time at their desks and computers instead of on their businesses. Productivity has gone backwards over the past couple of years – StatsNZ has the data.

For food to be cheaper, New Zealand needs a rethink. Productivity is key – producing more food for fewer inputs, including time, keeps the costs down. And having money that can be invested in the business, not just going on interest to the banks, is part of multifactor productivity.

Again, it has gone backwards in the past couple of years.

Imposing policy, whether through legislation or trying to get a jump on competitors, on behalf of society results in unintended consequences. The egg shortage and escalation in price is the example.

For all farmers and growers in New Zealand, market forces influence direction, and the market is saying that the cost of living is the number one concern.

Farmers and growers can’t respond if bogged down with paperwork and hampered by interest rates.

Nor can any business. A rethink will benefit more than just the primary sector.